My first cooking lessons began at the markets of France and continue there to this day. When I say “Shopping is Cooking,” I am saying literally that when you shop, you are beginning to cook. Each decision counts. From choosing the best ingredients, in season and at their peak of ripeness, to understanding the helpful words of the person who grew or produced the products, I begin to form the menu for a meal around the ingredients I buy. I ask the Poissonier (fish), the Boucher (meat), and the Fromager (cheese) for their advice.

“What’s good this week?”

“What’s special?”

“What did you eat this week?”

The dialogue between seller and buyer turns into a lesson between expert and student, and later from mentor to mentee. Of course, it helps to speak some French. “Some” is the important word here. You must at least try! Use these three little words you can easily learn to ask— “How do I cook this?”

“Comment cuisiner cela?”

My first true teacher-mentor relationship in France developed in the Marché Couvert in Agen 1988, the first season I arrived. It would continue through three generations of a family of produce vendors. This early memory is from A Culinary Journey in Gascony (1995), where I describe the first recipe lessons from Madame Elda Pagnan on how to cook a rabbit with local prunes—Lapin aux Pruneaux.

I remember my first Easter in Gascony and the first stay at the port in Agen with the Julia Hoyt. I was preparing to offer a special Sunday dinner meal for my bargemates, a sort of culinary joke—an Easter rabbit dinner. The joke was on me as well, since I had never prepared rabbit before. I walked from the old port to the marché couvert (the covered market) and screwed up my courage to buy a fresh rabbit from the poultry stall. There among the chickens, turkeys, guinea hens, and quail were whole rabbits, half rabbits, and rabbit pieces already skinned, cleaned, and ready to cook. But how? I put my purchase in my basket and looked around for a wise, friendly soul. There, behind a counter heaped with carrots, celery, parsley, lettuces, and other vegetables, was someone’s kindly grandmother, sorting through the wooden boxes of mushrooms.

“Excusez-moi, Madame ...” I fished in my basket, hauled up the rabbit by

the legs and asked in my very limited French, “How would you prepare this for dinner?” Without so much as a smile at my very foreign accent, she flew around the counter and started to list the ingredients as she popped them one at a time into a paper bag.“Two small onions, a handful of shallots, a few carrots ... “Plop, plop, plop, into the paper bag. A small bunch of thyme, two stalks of celery, and some parsley.

A small sack of prunes from the wooden drying rack were placed in my basket. Then, grabbing my hand, she led me across the market floor to the wine merchant and requested from him a half bottle of modest white wine. When he placed a small square plastic bottle the size of a soft drink on the counter and said “Deux francs et soixante-quinze centimes” (the equivalent of 50 cents or so), I began to protest that I could certainly afford a full bottle (and a better one at that!). Madame the Greengrocer looked me square in the eye and said, “It’s for the rabbit, dear, not the cook.” I bought both bottles (one for the cook, one for the rabbit) and with my recipe in the bag, I walked quickly back to the boat before I could forget the sequence of ingredients.

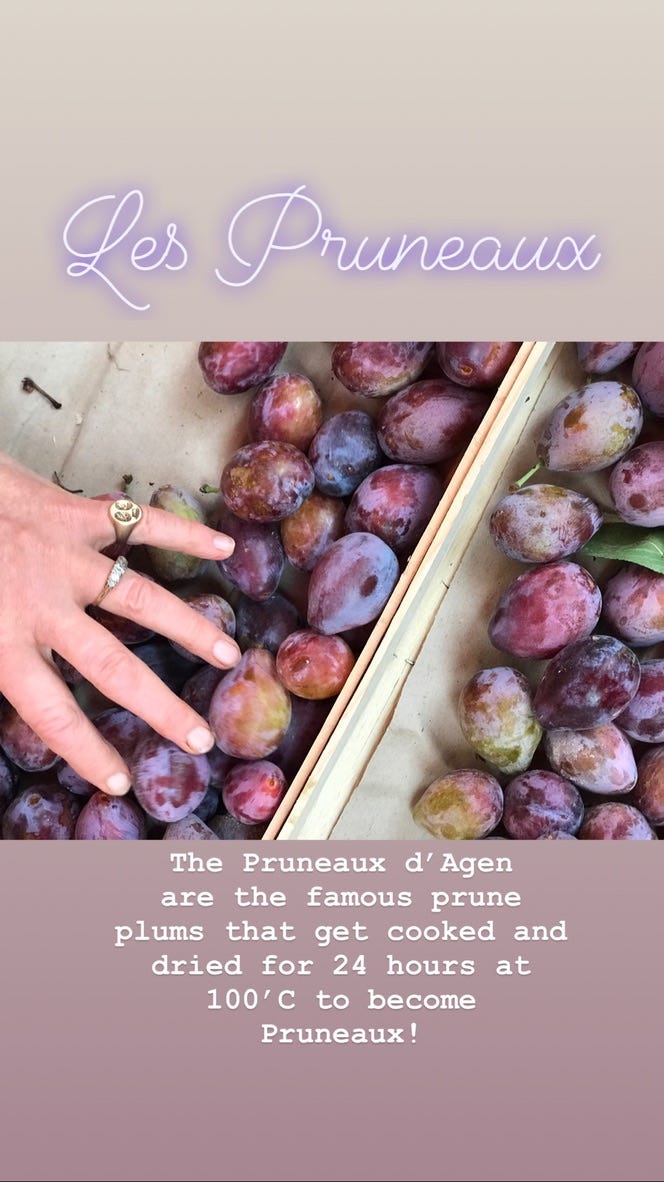

Of all the market stalls at my weekly markets, most are run by the producers themselves. The person growing and harvesting the strawberries and asparagus, the pork sausage and organic milk and cheese, the organic chickpeas and lentils, and the prized local Pruneaux d’Agen are also the people selling them to me. They have a special relationship with their products and farms, the Gascon terroir, and the neighbors. They have dirt engrained in their rough harvesting hands, and they watch the weather like hawks. Often, they have just one linear meter of a table laden with fresh eggs or a few chickens, ducks, or guinea hens.

In those early days, I didn’t have enough vocabulary in French to understand word by word, but I would look up recipes in French cookbooks to reinforce my understanding and ask any English-speaking French people for help. I also spent extra time at the markets building relationships. Buying even a small amount of cheese or meat each week, baskets of fresh salad greens, and kilos of seasonal fruit. I became that good customer that any market vendor would want—friendly and loyal. That meant that I shopped in the winter and in the bad weather, year in and year out, winter and summer. I came to shop, photograph, and discuss the weather. I asked questions and invited myself into their work. And then, one day, a miracle happened.

Meet Kakou et Françoise

In the larger weekly markets, there are always a few sprawling stalls of specialty items, such as tropical fruit and early-season produce from Spain and Portugal, or baskets of charcuterie, cheese, and pastries from neighboring regions like the Aveyron or the Pays Basque. Behind one of these long and tasty tables, I developed a long-standing relationship with a young couple, Françoise and Kakou, who sold premium charcuterie, bread, and pastries from the neighboring Aveyron region at the Nérac Saturday market. Their 20-foot-long tables were full of savory hams and saucissons, sweet, chewy walnut tarts, sturdy orange flower-scented brioches called fouaces, and the huge loaves of pain de campagne, which were parcelled out and weighed in thick slabs. (Funny, but I can’t find a single photograph, although I know I took many of Kakou hand-carving a giant Jambon de Coche—a ham made from giant sow.)

But I don’t need a photograph to remind me about the day when I was photographing him, working his long, thin ham knife gracefully around the bone and slipping the salty slab up and over the knob end, that he paused and said, “Kate, you should come behind here and see the face of humanity that I see.”

And just like that, with that one invitation, my perspective on all of the shopping I had done at markets changed. I went under the red and yellow umbrellas and behind the table as Kakou and Françoise sliced and weighed, exchanging the exact coins* and the village gossip with their other faithful customers. Later, I would travel with them to Rocamadour, a few hours away, to meet a beekeeper who supplied their Pain d’Épice. You could say our relationship as teachers and student was cemented in salt and honey.

*Every seller in any shop or market will ask if you have the exact change even when you hand them a 10€ note for something that costs 9,87€. That’s because an age-old law still on the French books imposes the onus of having the exact change on the buyer. In case of payment with bank notes or coins, the customer is supposed to give the exact change (article L 112-5 du Code monétaire et financier).

Seed to Sausage

And so the lessons continued. I would learn to cook pork from nose-to-tail. I would go on to The Chapolard family farm Baradieu and the butcher shop to butcher and make charcuterie- hams, saucissons, pâtés, and terrines. Butcher and pig farmer Dominque Chapolard explained they sold 20% charcuterie and 80% relationships. I would partner with Dominique, his wife Christiane Chapolard, and brothers Marc, Jacques, and Bruno to establish a rare professional charcuterie program. I’ll be writing about this intense learning period in a future chapter called Seed to Sausage.

Now, 13 years later, I relinquish the reins to former student and later assistant and food safety coach Nathan Gilmour in a legacy workshop in October of this year. You can read more about that at the Charcuterie Project website using the button below.

Lapin au Pruneaux De Mme. Pagnan (April 1988)

Serves 4-6

1 rabbit (a large stewing rabbit rather than a fryer if you can find one)

salt and freshly ground pepper

2 oz (55 g) ventrêche or bacon, diced

2 onions, cut in quarters

2 shallots, halved

2 tablespoons duck fat or oil

2 tablespoons flour

4 carrots, cut in chunks

2 branches celery, cut in chunks

2 to 3 sprigs fresh thyme

1 tablespoon chopped fresh parsley

18 prunes

1 bottle (750 ml) white wine minus 1 glass (although red wine works as well

1. Joint the rabbit into pieces and season with salt and pepper.

2. In a large stewing pan with a lid, place the bacon and cook over medium-high heat. Toss in the onions and shallots and cook until they start to brown. Remove from the pan and set aside.

3. Place the fat or oil in the hot pan and add the rabbit pieces. Sprinkle with the flour and brown on all sides. Add the carrots and celery and return the onions and shallots to the pan. Place the thyme, parsley, and half of the prunes in the pan. Pour the wine over the rabbit and make sure it is covered by the liquid, adding some water if needed.

4. Cover and simmer over very low heat for 45 minutes. Never let the mixture boil.

5. When the rabbit is very tender and starting to fall off of the bone, remove to a hot platter and hold in a warm oven. Add the remaining prunes to the sauce and, with the lid off, reduce the liquid by one-third by simmering briskly. Serve the rich, dark sauce over the rabbit with the vegetables and prunes alongside a generous helping of potatoes.

Finding France: A Culinary Memoir is an edible tale of a young traveling cook who gets stuck on a barge in France and stays to become a wise old woman with a head full of ideas on French food and cooking. Kate Hill—cook, teacher, mentor, and author—invites you into her world of French food as she learned over three dozen years of practice in the rural farmlands of Gascony. Read more here.

Kate Hill is the author of over a dozen cookbooks, including A Culinary Journey in Gascony, Cassoulet: A French Obsession, and A Gascon Year Series of 12 recipe and story volumes (available here). Published in America’s Best Food Writing 2019, curated by Samin Nosrat, Kate Hill has written for Saveur Magazine and The Los Angeles Times. Kate and her cooking, butchery, and charcuterie programs have been featured in Bon Appétit, Food and Wine, Condé Nast Traveler, The Washington Post, The New York Times, Boston Globe, Faire magazine, My French Country Home, and countless websites.

Rabbit is one of my favorite proteins to cook with. I have a couple stellar rabbit recipes on my regular blog (not Substack) if you're looking for even more ways to enjoy it! I usually trade homemade pies for rabbits with a hunter friend. :)

Prunes! Something constantly staring me in the face and not thinking to use. Sadly, not Agen ones. I bought a whole skinned rabbit here in Italy, not so long ago, cooking it with juniper berries and rosemary (bayleaves seem to be famine or feast), a ragù with pappardelle. The butchers here are shocked when they are denied the opportunity to use their cleavers, but then again, they are also surprised by a man shopping and cooking. A lovely post, thank you. I will save your recipe for next time.