A Foraged Life and Wild French Recipes

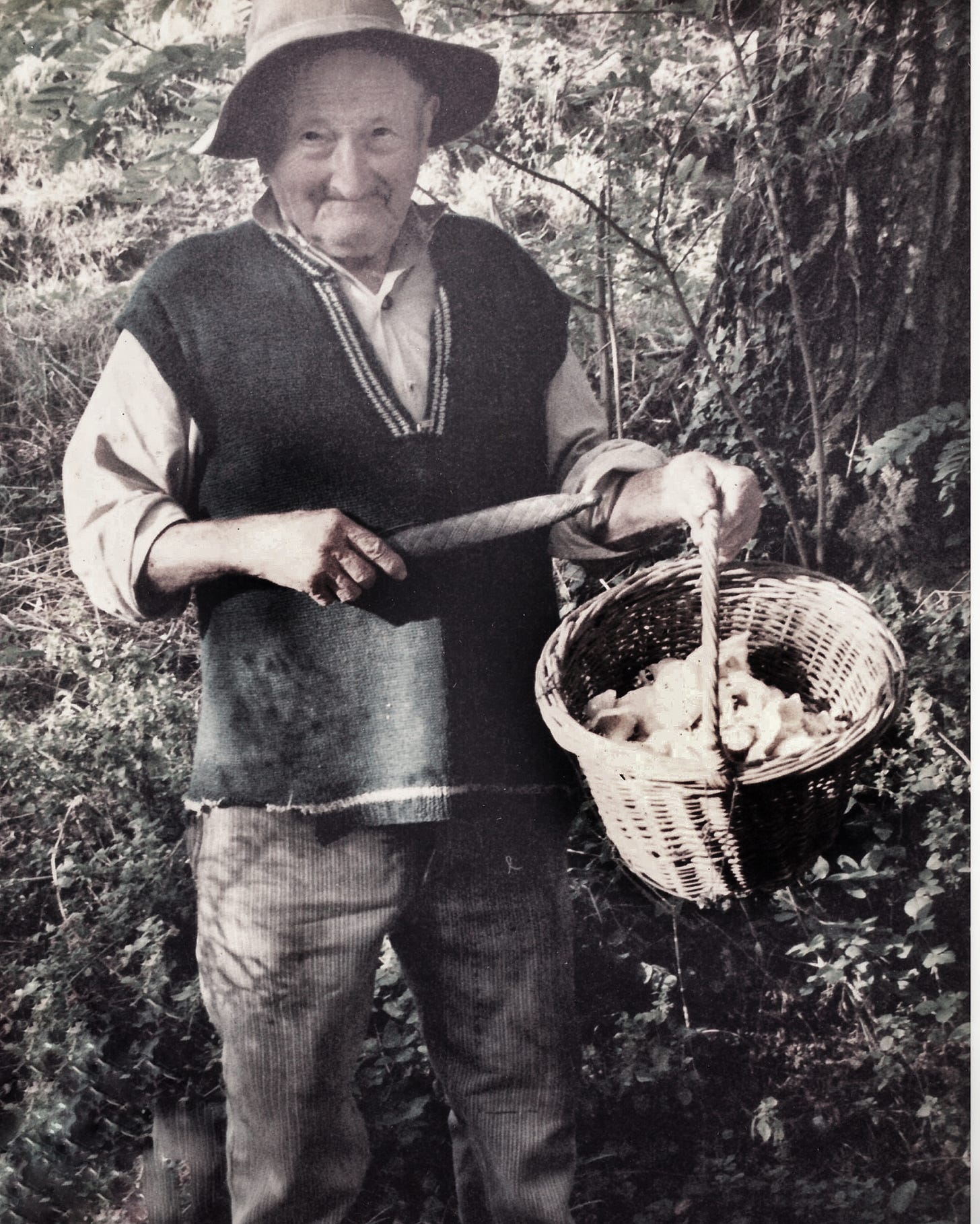

Finding France with Monsieur Dupuy, the Mushroom Hunter.

In the “Portraits” section of ‘Finding France,’ I introduce you to my mentors and teachers, the strangers, the intimates, the professionals, and housewives who have guided and taught me along my culinary journey. Remember, you can read ‘Finding France’ in any order you like. Like most of our memories, it’s not chronological.

A Portrait of a Foraged Life—Old Man Dupuy

Long before I planted seeds for my first potager, there was food popping out of the ground at Camont—watercress, wild leeks, and mushrooms. I watched and followed my old neighbor, the former owner of Camont, M. Dupuy, to learn where he found those savory bits he tucked into a basket and then tried to race him to those spots next time. Learning by watching has always been my main approach to cooking, too.

When I took over the land and ruins of a farmhouse, piggery, chicken coop, pigeonnier, and barn in 1989—this farm called Camont since 1724, Monsieur Dupuy was the first of the neighbors I met. He had married the farm and the farmer’s daughter, Simone, sometime after the war (1940s) and had a daughter, Monique, in the same year I was born—in 1951. Together with the in-laws, they tended the fields, orchards, and animals of Camont, including the huge white oxen that plowed the fields. They lived in a tile-roofed, three-room house, each room lit by a single hanging bulb. There was no running water nor indoor toilet; instead, a spring that he called la fontaine provided drinking and washing water as it ran free, clear, and cold through the stone lavoir against the hill. A wide open fireplace served for heating and cooking; old barrels and huge oak vats were for making wine; duck fat yellow-glazed confit pots and broken furniture still rested on the cool, beaten clay floor carved into the hillside. I unearthed broken crockery and old glass bottles that had been tossed alongside the remains of a wood oven, which provided bread for the three families working the farm. More than a piece of property, this is what I bought—history.

Long before I came along, Monique Dupuy moved her elderly parents into a modern cottage across the road from les ruines. And although he slept and ate there, M. Dupuy never let his small, sharp eyes leave the property until he felt I had it well in hand. From the beginning, there was a mythic, mystic feeling about this place, and Old Man Dupuy was its ancient yet timeless gardien for all the seasons that he and I shared here. It was as if he came thumping down the towpath, two canes in syncopation, directly from the late 19th century to share with me the old French ways, a tattered canvas bag across his chest full of gleaned corn kernels to feed the wild ducks who nested along the canal.

Old man Dupuy was one of my earliest teachers about country life in Gascony. Nestled against the northwest-flowing Garonne River, and later bisected by the canal, this ghost of a farm was where my understanding of the food culture I was stumbling across began. I bought the land to have a place to park my barge in the quiet countryside, but it became the key to unlocking everything I would come to know about cooking in France. The kitchen didn’t even have a roof yet, but I was already beginning to understand its importance.

Without any pretense, M. Dupuy explained to me in a jumble of Gascon and old French patois how to purge the gathered escargots before cooking with rose petals from the first bushes I planted. And he showed me how to divine for water with a pendule or pocket watch on a delicate gold chain. Somehow, with just sign language and lots of grimacing from his toothless mouth, he taught me, and I learned how to steward this parcel of Gascon culinary history season by season.

And so I learned on early mornings, walking through the garden, to gather some snails before old man Dupuy could take them all and sell them back to me for 10 francs, his cigarette money. I drilled the shallow garden well at the exact spot he hovered over a bit too long as the chain of his pocket watch danced a slow, steady circle. I learned to say adishatz (‘go with God’ in Gascon) instead of au revoir. I stole some of my own watercress for soup from the cold spring at la fontaine while M. Dupuy bundled the rest with recycled string and drove it to sell at the Saturday market in Le Passage. Off he’d go on his Mobylette, towing a small trailer full of escargots, bunches of peppery cressons for salad and soups, and small knotted plastic bags of field corn for birds. I learned by watching his practice and repeated until I owned it.

Wild Recipes

One summer, long after we had become friends, I built a scarecrow that looked like Monsieur Dupuy. My mustachioed griffon Dupont would bark at it each time he saw the antique linen shirt flapping on the broken rake in the bean patch. It must have seemed to his birddog brain that the mismatched rubber boots topped by a dented pith helmet and supported on two hazel canes had come to life in the potager and were trying to ‘steal’ the cassoulet beans.

There would be many more lessons about country living and food over the years before M. Dupuy just disappeared into the November fog one year while I was away traveling. The lessons learned remain, and I pass them on to my students, residents, and friends who keep the revolving door of Camont open. We cook à la Camont, meaning with whatever is at hand.

Like the foraged food he gathered, I gleaned many of these recipes from the wild. “Wild Recipes” are those gathered at someone's kitchen table or overheard at a market stall. Or from old ladies in blue housedress/aprons exchanging little trucs at a farm table while butchering the yearly pig. Inspired by a sense of pride or a penchant for a petite surprise to one-up their neighbors, les madames talked and talked and filled my head with tales of old France and old kitchens.

“Only use shallots rather than onions…much milder.”

“Good water makes good soup. I use water from la source—spring water.”

“My Belle-Mère always added an orange peel to her Daube de Boeuf.”

These small declarations were a sort of love wielded like a paring knife instead of a broadsword—proprietorial and honorable kitchen jousting. When I look back at my younger self, eager to acquire French skills and a working kitchen vocabulary, I remember the sing-song of these farmwives, market vendors, and café owners rasping out a list of ingredients for a beef stew or a simple technique to make the silkiest crème de citron. I hear it echoed now in my 70-year-old voice, telling a new stagière or visiting resident just how to chop the shallots—not too fine, or why they should stop stirring the pot so much. Maybe I shush everyone, turn down the music, and ask them to be quieter to listen to the pan more. I caution them to look around and learn. France is everywhere.

M. Dupuy held the history of Camont in his pockets. He used a carved wooden knife to poke around the grassy towpath for mushrooms called Peupliers filling plastic bag after plastic bag with the smallest champignons imaginable. Peupliers grow on the roots of the towering Poplar trees and still appear on the stumps that remained following the big wind storms of the Millenial turning. Pholiote du peuplier or Cyclocybe aegerita sprout in abundance after the first rains in the spring and again in the fall. While others wait for the more prized cèpes or girolles, I anticipate that this weekend, they’ll return after this first rain that we have had in weeks.

As small as tiny round brown buttons or opened flat and cream-colored the size of your palm, peupliers are best quickly sautéed in some duck fat, folded into an omelet, or smothered with a persillade—that ubiquitous southwestern garnish of finely chopped parsley and raw garlic.

On these autumn mornings, as tendrils of mist lift from the canal, I swear I can still see M. Dupuy walking along the towpath, quacking to the wild mallards as he dribbles handfuls of stolen corn to them. They follow him between the trees, waggling their feathered behinds, and echo his whispered, “Coin, coin. Coin, coin,” the sound that French ducks make. Adischatz, M. Dupuy!

Coming Next:

Narrative Recipe No.2. A simple Cassoulet—a primer on beans and charcuterie

Recipes File Archives No.2. Make M. Dupuy’s soup from the recipe here: Filet de Poissons a la Aigue Morte, Small Savory Pies, la Bonne Soupe de Monsieur Dupuy, Velouté de Potimarron—a squash and chestnut soup, a Simple Cassoulet. (For paid subscribers)

Q&A Videos with Kate. Starting at the end of the month.

Are you enjoying Finding France: a Memoir in Small Bites? Why not become a paid subscriber and help support this year of good food and memories? Like buying a book in a bookstore, Substack is the most indie of all bookshops! When you buy a year’s subscription, it is like buying one magazine every month or sharing a glass of wine with a friend. I hope that you will read and cook along as I take you on a four-season, 36-year journey as I was Finding France. Remember, paid subscribers receive all access to the Recipe Files Archive, Club Camont Community discussions on Chat, and Q&A videos with Kate.

Finding France: A Memoir in Small Bites is an edible tale of a young traveling cook who gets stuck in France and stays to become a wise old woman with a head full of ideas on French food and cooking. Kate Hill—cook, teacher, mentor, and author—invites you into her world of French food as learned over three dozen years of practice in the rural farmlands of Gascony.

Kate Hill is the author of over a dozen cookbooks, including A Culinary Journey in Gascony, Cassoulet: A French Obsession, and A Gascon Year Series of 12 recipe and story volumes (available here). Featured in America’s Best Food Writing 2019, curated by Samin Nosrat, Kate has written for Saveur Magazine, The Los Angeles Times, and been featured in Bon Appétit, Food and Wine, Condé Nast Traveler, The Washington Post, The New York Times, My French Country Home, and countless websites.

Utterly brilliant, Kate, and of course I remember the unforgettable M. Dupuy and am so glad I had a chance to meet him long, long ago. I love all these stories but especially the sense of an emerging sensibility, your own, as you encounter the place and the people, the land and the seasons. Keep it coming!

Wonderful story thank you for sharing Kate! I love M. Dupuy’s recipe for purging escargot with rose petals. Does the flavour delicately infuse the cooked escargot? My neighbour starved hers in a finely meshed cage. They were too chewy and tough for my palette - and bland!

I’m so enjoying your stories! Thankyou! 😊